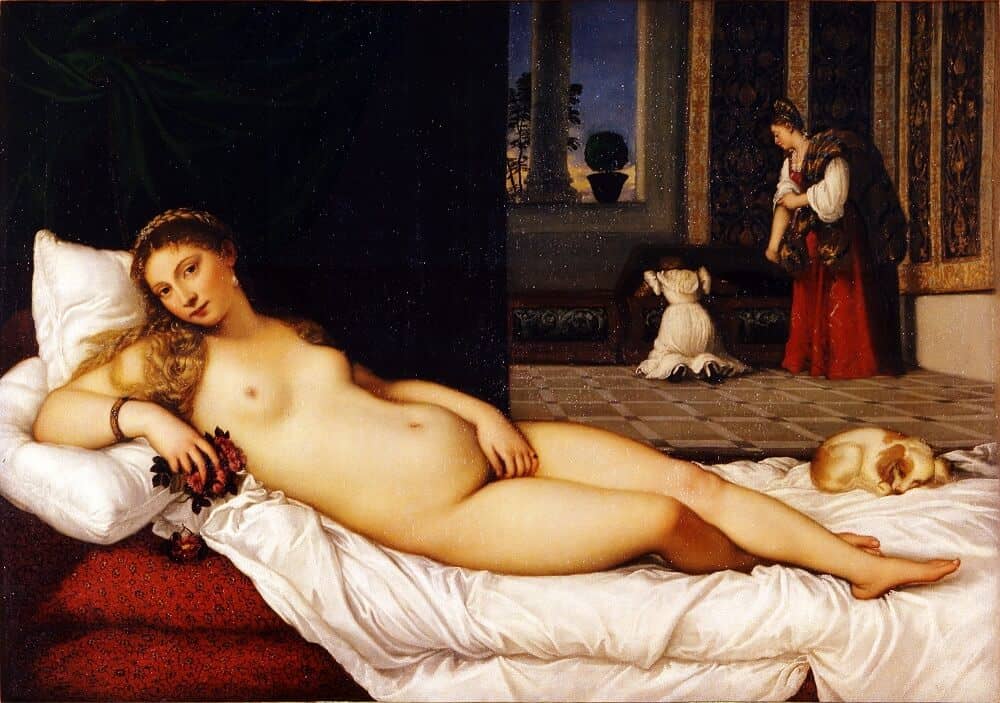

Venus of Urbino, 1538 by Titian

Toward the beginning of his career Titian had brought to completion Giorgione's unfinished canvas of a nude Venus asleep in a landscape; some twenty-five years later he adapted the central

motif of the recumbent nude to a new setting and transformed its meaning by domesticating that pastoral deity. Giorgione's Venus - withdrawn in a private dream of love that we can share,

to a degree, only by an effort of the imagination - has been brought indoors ; fully awake now and aware of her audience, she displays her charms in a deliberately public proclamation of

love. Nudity, in the context of the interior setting and her jeweled adornment, is evidently not her normal state; she is, rather, naked, awaiting the garments that will clothe her.

This goddess clearly celebrates a different set of values, and her function, more social than poetic, is articulated by her surrounding attributes. She holds a bunch of roses, and on the

window ledge in the background a myrtle plant, in perpetual bloom, is pointedly silhouetted against the glowing sky. These floral symbols, traditionally associated with Venus, define the

very special kind of love she here represents: not merely carnal desire, but the more fruitful passion of licit love; not the quickly sated lust of the body, but the permanent bond of marital

affection. The little dog curled up at her feet in contented slumber overtly symbolizes that ideal fidelity.

Adding a naturalistic anecdotal dimension to the sensuous symbolism of the main motif, the enframed background scene of maids at an open cassone, or marriage chest, confirms the social

significance of the image. Guidobaldo II della Rovere, who was awaiting delivery of the picture to Urbino in 1538, may well have ordered it - some years earlier, to judge by his evident

impatience - to celebrate his marriage of 1534.

Refining a favorite type of compositional structure especially important in his works of the 1530s, Titian here further explores a compositional problem to which he would return in later

paintings. The architectural regularity and stability of the setting provides a contrasting backdrop for the organic curves of the female form. The measured coordinates of the architecture,

the pavement, and the wall hangings are summarized in the neat bisection of the field by the dark screen, whose vertical edge focuses on the fertile center of the love goddess. Thus divided

on a large scale, the field is unified by the distribution of color and by a host of smaller-scale formal correspondences, especially the various floral patterns - on the couch, and the

background cassoni and tapestries - which derive visually from the cluster of roses and share the virtual size of those flowers although, in reality, they differ in actual dimensions.