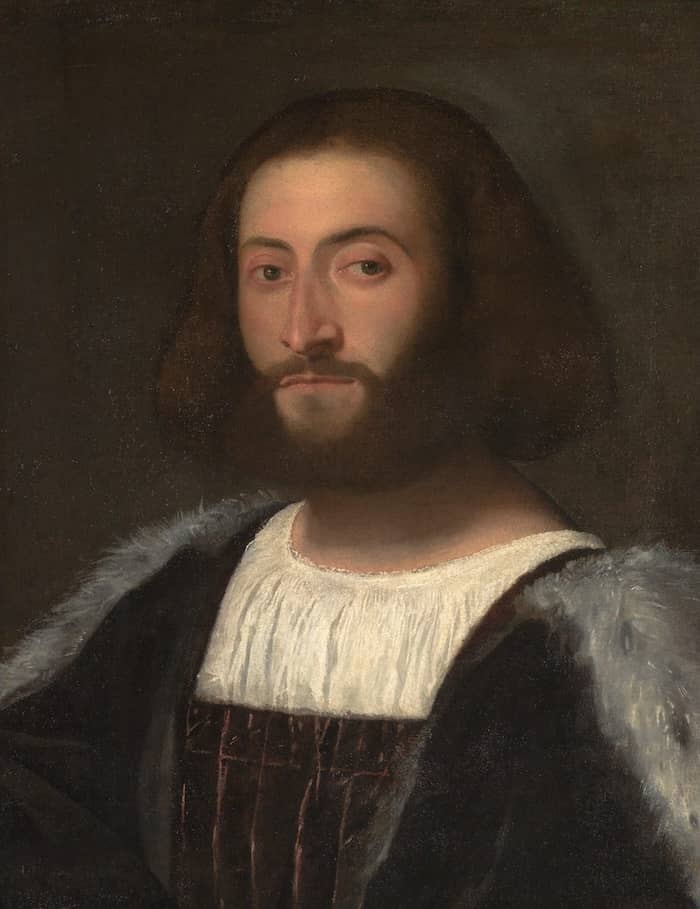

Portrait of a Man, 1512 by Titian

In its chromatic as well as its compositional relationships, the cool elegance of this portrait perfectly describes the classical ideal of style Titian had defined for himself in the course

of his Paduan year. While in a general way the aesthetic of the image shares some qualities with Giorgione's inventions in portraiture - the use of the parapet, the spatial complexity of

the contrapposto, even a certain softening of the physiognomic features - these have been developed along more rigorously structured lines. The vertical stability of the axis of the figure,

emphasized by the level turn of the head, establishes a critical central coordinate against which spatial variations are measured. The movement of the figure, controlled by an overt respect

for planar relationships, seems less serpentine than faceted. The magnificently sleeved arm, while significantly breaking over the edge of the parapet and hence, by implication, beyond the

picture plane, thrusting forward and back into space, nonetheless maintains the continuity of that plane - partly by the value distribution of the luxurious blue satin.

Within the broad stability of the pyramidal construction there is a highly sophisticated visual play of internal correspondences. The two great areas of light, the face and the costume,

are each enframed by a darker element, which at once contains them and defines the larger silhouette of the figure. The fur-lined cloak draped with such studied casualness over the far

shoulder creates a deep resonance of tone against which the satin sleeve is played off - as the profile of the cloak itself comments on the outline of the sleeve. The illuminated face of

the sitter receives added strength from the dynamic profile of the surrounding hair and beard, which complement the larger shapes of the full figure.

If much of the impact of this portrait depends upon its large-scale relationships, these all serve to accentuate the psychological locus of the image, the highly articulate face and

especially the direct encounter of those sharply alert and intelligent eyes. The very assertiveness of this entire configuration, the quality of the pose as well as the calm confidence of

the physiognomic expression, has led to the tantalizing suggestion that this unknown sitter may in fact represent Titian himself. (An older identification as the poet Ludovico Ariosto has

long been abandoned.) The picture was known to Rembrandt and Van Dyck in the seventeenth century, and did, indeed, inspire self-portraits by those masters.